Konarkn

Sun Temple

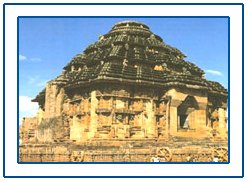

The

magnificent Sun Temple at Konark is the culmination

of Orissan temple architecture, and one of the most stunning

monuments of religious architecture in the world. The poet

Rabindranath Tagore said of Konark that 'here the language

of stone surpasses the language of man', and it is true that

the experience of Konark is impossible to translate into words.

The

massive structure, now in ruins, sits in solitary splendour

surrounded by drifting sand. Today it is located two kilometers

from the sea, but originally the ocean came almost up to its

base. Until fairly recent times, in fact, the temple was close

enough to the shore to be used as a navigational point by

European sailors, who referred to it as the 'Black

Pagoda'.

Built by King Narasimhadeva in the thirteenth century, the

entire temple was designed in the shape of a colossal chariot,

carrying the sun god, Surya, across the heavens. Surya has

been a popular deity in India since the Vedic period and the

following passages occur in a prayer to him in the Rig Veda,

the earliest of sacred religious text:"Aloft his beams

now bring the good, Who knows all creatures that are born,

That all may look upon the Sun. The seven bay mares that draw

thy car, Bring thee to us, far-seeing good, O Surya of the

gleaming hair. Athwart in darkness gazing up, to him the higher

light, we now Have soared to Surya, the god Among gods, the

highest light."

So

the image of the sun god traversing the heavens in his divine

chariot, drawn by seven horses, is an ancient one. It is an

image, in fact, which came to India with the Aryans, and its

original Babylonian and Iranian source is echoed in the boots

that Surya images, alone among Indian deities, always wear.

The

idea of building an entire temple in the shape of a chariot,

however, is not an ancient one, and, indeed, was a breathtakingly

creative concept. Equally breathtaking was the scale of the

temple which even today, in its ruined state, makes one gasp

at first sight. Construction of the huge edifice is said to

have taken 12 years revenues of the kingdom.

The

main tower, which is now collapsed, originally followed the

same general form as the towers of the Lingaraja and Jagannath

temples. Its height, however, exceeded both of them, soaring

to 227 feet. The jagmohana (porch) structure itself exceeded

120 feet in height. Both tower and porch are built on high

platforms, around which are the 24 giant stone wheels of the

chariot. The wheels are exquisite, and in themselves provide

eloquent testimony to the genius of Orissa's sculptural tradition.

At

the base of the collapsed tower were three subsidiary shrines,

which had steps leading to the Surya images. The third major

component of the temple complex was the detached natamandira

(hall of dance), which remains in front of the temple. Of

the 22 subsidiary temples which once stood within the enclosure,

two remain (to the west of the tower): the Vaishnava Temple

and the Mayadevi Temple. At either side of the main temple

are colossal figures of royal elephants and royal horses.

Just

why this amazing structure was built here is a mystery. Konark

was an important port from early times, and was known to the

geographer Ptolemy in the second century AD. A popular legend

explains that one son of the god Krishna, the vain and handsome

Samba, once ridiculed a holy, although ugly, sage. The sage

took his revenge by luring Samba to a pool where Krishna's

consorts were bathing. While Samba stared, the sage slipped

away and summoned Krishna to the site. Enraged by his son's

seeming impropriety with his stepmothers, Krishna cursed the

boy with leprosy. Later he realized that Samba had been tricked,

but it was too late to withdraw the curse. Samba then travelled

to the seashore, where he performed 12 years penance to Surya

who, pleased with his devotion, cured him of the dreaded disease.

In thanksgiving, Samba erected a temple at the spot.

In

India, history and legend are often intextricably mixed. Scholars

however feel that Narasimhadeva, the historical builder of

the temple, probably erected the temple as a victory monument,

after a successful campaign against Muslim invaders.

In

any case, the temple which Narasimhadeva left us is a chronicle

in stone of the religious, military, social, and domestic

aspects of his thirteenth century royal world. Every inch

of the remaining portions of the temple is covered with sculpture

of an unsurpassed beauty and grace, in tableaux and freestanding

pieces ranging from the monumental to the miniature. The subject

matter is fascinating. Thousands of images include deities,

celestial and human musicians, dancers, lovers, and myriad

scenes of courtly life, ranging from hunts and military battles

to the pleasures of courtly relaxation. These are interspersed

with birds, animals (close to two thousand charming and lively

elephants march around the base of the main temple alone),

mythological creatures, and a wealth of intricate botanical

and geometrical decorative designs. The famous jewel-like

quality of Orissan art is evident throughout, as is a very

human perspective which makes the sculpture extremely accessible.

The temple is famous for its erotic sculptures, which can

be found primarily on the second level of the porch structure.

The possible meaning of these images has been discussed elsewhere

in this book. It will become immediately apparent upon viewing

them that the frank nature of their content is combined with

an overwhelming tenderness and lyrical movement. This same

kindly and indulgent view of life extends to almost all the

other sculptures at Konark, where the thousands of human,

animal, and divine personages are shown engaged in the full

range of the 'carnival of life' with an overwhelming sense

of appealing realism.

The

only images, in fact, which do not share this relaxed air

of accessibility are the three main images of Surya on the

northern, western, and southern facades of the temple tower.

Carved in an almost metallic green chlorite stone (in contrast

to the soft weathered khondalite of the rest of the structure),

these huge images stand in a formal frontal position which

is often used to portray divinities in a state of spiritual

equilibrium. Although their dignity sets them apart from the

rest of the sculptures, it is, nevertheless, a benevolent

dignity, and one which does not include any trace of the aloof

or the cold. Konark has been called one of the last Indian

temples in which a living tradition was at work, the 'brightest

flame of a dying lamp'. As we gaze at these superb images

of Surya benevolently reigning over his exquisite stone world,

we cannot help but feel that the passing of the tradition

has been nothing short of tragic.

Approach

: By air to Bhubaneswar, Konark is 65 km from

Bhubaneswar by road.

|